|

Writer Officina Blog

Writer Officina Blog

|

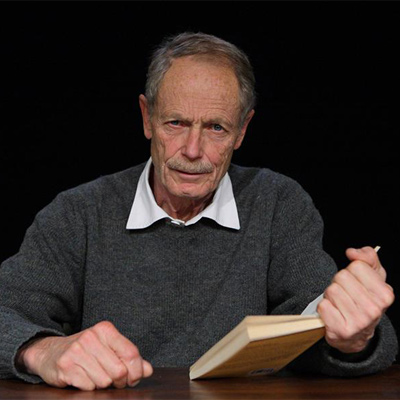

Erri De Luca. Nato a Napoli nel 1950, ha scritto narrativa,

teatro, traduzioni, poesia. Il nome, Erri, è la versione italiana

di Harry, il nome dello zio. Il suo primo romanzo, “Non ora, non

qui”, è stato pubblicato in Italia nel 1989. I suoi libri

sono stati tradotti in oltre 30 lingue. Autodidatta in inglese, francese,

swahili, russo, yiddish e ebraico antico, ha tradotto con metodo letterale

alcune parti dell’Antico Testamento. Vive nella campagna romana dove

ha piantato e continua a piantare alberi. Il suo ultimo libro è "A

grandezza naturale", edito da Feltrinelli.

Erri De Luca. Nato a Napoli nel 1950, ha scritto narrativa,

teatro, traduzioni, poesia. Il nome, Erri, è la versione italiana

di Harry, il nome dello zio. Il suo primo romanzo, “Non ora, non

qui”, è stato pubblicato in Italia nel 1989. I suoi libri

sono stati tradotti in oltre 30 lingue. Autodidatta in inglese, francese,

swahili, russo, yiddish e ebraico antico, ha tradotto con metodo letterale

alcune parti dell’Antico Testamento. Vive nella campagna romana dove

ha piantato e continua a piantare alberi. Il suo ultimo libro è "A

grandezza naturale", edito da Feltrinelli. |

Patrizia Rinaldi si è laureata in Filosofia all'Università

di Napoli Federico II e ha seguito un corso di specializzazione di scrittura

teatrale. Vive a Napoli, dove scrive e si occupa della formazione dei ragazzi

grazie ai laboratori di lettura e scrittura, insieme ad Associazioni Onlus

operanti nei quartieri cosiddetti "a rischio". Dopo la pubblicazione

dei romanzi "Ma già prima di giugno" e "La

figlia maschio" è tornata a raccontare la storia

di "Blanca", una poliziotta ipovedente da cui è

stata tratta una fiction televisiva in sei puntate, che andrà in

onda su RAI 1 alla fine di novembre.

Patrizia Rinaldi si è laureata in Filosofia all'Università

di Napoli Federico II e ha seguito un corso di specializzazione di scrittura

teatrale. Vive a Napoli, dove scrive e si occupa della formazione dei ragazzi

grazie ai laboratori di lettura e scrittura, insieme ad Associazioni Onlus

operanti nei quartieri cosiddetti "a rischio". Dopo la pubblicazione

dei romanzi "Ma già prima di giugno" e "La

figlia maschio" è tornata a raccontare la storia

di "Blanca", una poliziotta ipovedente da cui è

stata tratta una fiction televisiva in sei puntate, che andrà in

onda su RAI 1 alla fine di novembre. |

Gabriella Genisi è nata nel 1965. Dal 2010 al 2020,

racconta le avventure di Lolita Lobosco. La protagonista è

un’affascinante commissario donna. Nel 2020, il personaggio da lei

creato, ovvero Lolita Lobosco, prende vita e si trasferisce dalla

carta al piccolo schermo. In quell’anno iniziano infatti le riprese

per la realizzazione di una serie tv che si ispira proprio al suo racconto,

prodotta da Luca Zingaretti, che per anni ha vestito a sua volta proprio

i panni del Commissario Montalbano. Ad interpretare Lolita, sarà

invece l’attrice e moglie proprio di Zingaretti, Luisa Ranieri.

Gabriella Genisi è nata nel 1965. Dal 2010 al 2020,

racconta le avventure di Lolita Lobosco. La protagonista è

un’affascinante commissario donna. Nel 2020, il personaggio da lei

creato, ovvero Lolita Lobosco, prende vita e si trasferisce dalla

carta al piccolo schermo. In quell’anno iniziano infatti le riprese

per la realizzazione di una serie tv che si ispira proprio al suo racconto,

prodotta da Luca Zingaretti, che per anni ha vestito a sua volta proprio

i panni del Commissario Montalbano. Ad interpretare Lolita, sarà

invece l’attrice e moglie proprio di Zingaretti, Luisa Ranieri. |

|

Altre interviste su Writer

Officina Magazine

|

Manuale di pubblicazione Amazon KDP. Sempre più autori

emergenti decidono di pubblicarse il proprio libro in Self su Amazon KDP,

ma spesso vengono intimoriti dalle possibili complicazioni tecniche. Questo

articolo offre una spiegazione semplice e dettagliata delle procedure da

seguire e permette il download di alcun file di esempio, sia per il testo

già formattato che per la copertina.

Manuale di pubblicazione Amazon KDP. Sempre più autori

emergenti decidono di pubblicarse il proprio libro in Self su Amazon KDP,

ma spesso vengono intimoriti dalle possibili complicazioni tecniche. Questo

articolo offre una spiegazione semplice e dettagliata delle procedure da

seguire e permette il download di alcun file di esempio, sia per il testo

già formattato che per la copertina. |

Self Publishing. In passato è stato il sogno nascosto

di ogni autore che, allo stesso tempo, lo considerava un ripiego. Se da

un lato poteva essere finalmente la soluzione ai propri sogni artistici,

dall'altro aveva il retrogusto di un accomodamento fatto in casa, un piacere

derivante da una sorta di onanismo disperato, atto a certificare la proprie

capacità senza la necessità di un partner, identificato nella

figura di un Editore.

Self Publishing. In passato è stato il sogno nascosto

di ogni autore che, allo stesso tempo, lo considerava un ripiego. Se da

un lato poteva essere finalmente la soluzione ai propri sogni artistici,

dall'altro aveva il retrogusto di un accomodamento fatto in casa, un piacere

derivante da una sorta di onanismo disperato, atto a certificare la proprie

capacità senza la necessità di un partner, identificato nella

figura di un Editore. |

Scrittori si nasce. Siamo operai della parola, oratori,

arringatori di folle, tribuni dalla parlantina sciolta, con impresso nel

DNA il dono della chiacchiera e la capacità di assumere le vesti

di ignoti raccontastorie, sbucati misteriosamente dalla foresta. Siamo figli

della dialettica, fratelli dell'ignoto, noi siamo gli agricoltori delle

favole antiche e seminiamo di sogni l'altopiano della fantasia.

Scrittori si nasce. Siamo operai della parola, oratori,

arringatori di folle, tribuni dalla parlantina sciolta, con impresso nel

DNA il dono della chiacchiera e la capacità di assumere le vesti

di ignoti raccontastorie, sbucati misteriosamente dalla foresta. Siamo figli

della dialettica, fratelli dell'ignoto, noi siamo gli agricoltori delle

favole antiche e seminiamo di sogni l'altopiano della fantasia. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Blog

|

|

|

|

Biblioteca New

|

|

|

|

Biblioteca All

|

|

|

|

Biblioteca Top

|

|

|

|

Autori

|

|

|

|

Recensioni

|

|

|

|

Inser. Romanzi

|

|

|

|

@ contatti

|

|

|

Policy Privacy

|

|

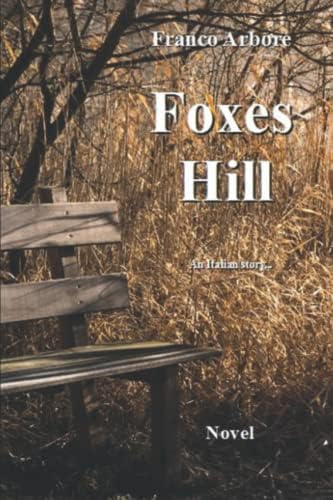

Foxes Hill

Foxes Hill

|

It is three o'clock in the afternoon, and we are in the middle of June 1955.

It is three o'clock in the afternoon, and we are in the middle of June 1955.

School has just finished two days ago and I am leaving for a vacation, which I expect will be very long: all summer.

I go to Rocchetta Sant'Antonio to find my maternal grandmother Filomena; Dad accompanied me by car, a Fiat 500C, to Trani: at the bus stop for Cerignola, in Bisceglie square.

It is hot and, where we are, there is no shade under which to shelter from the sun, there is not even a shop awning lowered.

We are in Puglia - Italy and in this period, here with us, it cannot be otherwise.

Meanwhile, while we wait for the bus, Dad continues with his advice and recommendations as he had already done from Corato.

My mother, on the other hand, when I left the house hugged and kissed me several times: a few tears ran down her face.

This is my first time traveling alone; I am only seven years old and I have not even made them.

My father Antonio is really a good person, it is neither naive nor inexperienced, I understand that he is a little worried, but he knows very well that I would have listened and followed his advice.

I understand it well: after all, I am still a child and it is not usual for children to travel alone.

************

The journey, perhaps for those times and for the means in circulation at the time, would have been quite long even if it would have been just a hundred kilometers.

It will however, be a journey with too many stops, too many bus changes and, above all, too many drivers to whom trust me.

************

I have the feeling that at the last moment he can change his mind and never let me leave.

The journey is long and he had already explained this to me before. It is a vacation, which they have promised me for some time, and the arrangements with grandmother have already been made.

How many nights have I dreamed of this travel!

At the beginning my parents, like last year, had decided that they would accompany me, but a few days before my departure, my mother told me that, perhaps, I would not go to Rocchetta because my father could no longer accompany me: he would have done it but he had more to do than usual.

I look my father in the eye showing him all my fear, but he see and looks at me: he understood that maybe I am about to cry and immediately reassures me by stroking my hair.

However, we wait for the bus; Father therefore continues to give me directions: "Be careful that, in Cerignola, at the cathedral stop, you have to get off the bus and wait for that for Candela that will come soon after".

"Then when you arrive at Candela station, get off and wait for the Lapalorcia company bus, which will take you to Rocchetta; there you go straight to the grandmother's house".

"Be careful with the suitcase, do not make your grandmother angry, and be good, please!”

He continues as I nod briskly, wanting him to understand that he can rest assured.

Finally, the bus arrives: a screech of brakes, a puff of compressed air and it is stopped; the doors open, and the driver gets out.

End of advice and recommendations, one more caress and I go up; I am the only one going up, there is no one else going up.

As I decide where to sit, I hear my father talking to the man: evidently, he is entrusting me to him.

With a nod of understanding, they greet each other; a final farewell and the doors close, the bus departs.

Not even a kiss: I did not expect it and, after all, I never received any from him, at least when awake as well as, after all, not even as a grandmother.

Few travelers: two men and three women, seated each on his own, and divided into the two rows of central seats.

For a moment, I look at them: a young-looking woman wipes her forehead with a handkerchief: a large handkerchief.

One of the men, hat on his head and mustache like King Vittorio Emanuele II, smokes.

I notice that everyone is looking at me; he travels alone so small, I think they are thinking; I get a smile from everyone and I smile too.

I sit behind the driver, near the window.

I put the suitcase on the seat beside it, and with my right hand, I hold the handle tight.

Now we are out of town, I have an excellent view; I watch the road go by, the driver's maneuvers, the odometer, generally stopped at forty except in some long straights where the speed of the vehicle reaches up to fifty kilometers per hour.

The engine, in front under the hood, seems to sing; the driver also sings: "Grazie dei Fiori" (Thank for the flowers), a song sung by Nilla Pizzi, which I learned later.

I speak to the driver: "I have to get off at Cerignola, near the cathedral!"; "Okay, I know!” he replies without taking his eyes off the road.

After, nothing, not even a question.

Every now and then, I observe the others: the smoker smokes, the one with the handkerchief has, in the meantime, pulled out a fan that quickly waves; the rest nothing, they are impassive they look like ice.

From the window, I see the landscape and at the same time, I glimpse the countryside flowing, consisting mainly of olive groves and vineyards; then we also cross the Ofanto River, which, at that point, seems quite wide to me.

After which large expanses of ripe wheat begin to flow which, driven by a light breeze, sways in several directions.

In Cerignola the bus stops: "This is where you have to get off", they say in chorus, driver and passengers; in the meantime, two of them go down with me.

"Be careful," says the woman with the fan and then “wait here and do not move!” the smoker, the one with the big mustache, recommends me.

The two of them greet me: "Ciao!" (Hello!)

I reply with my hello, and then they walk away.

I never saw them again.

Every now and then, I thought of them, of their smiles; today I do not remember their faces anymore.

The driver waved goodbye to me, went up, and the bus started again: destination Foggia, nobody got on.

At the departure, the bus hits me with a cloud of black smoke: instinctively I turn around to avoid breathing it and I see the cathedral.

It is huge, it seems to me, and overlooks a large square: it has a dome the same as that of St. Peter's in Roma, which I only saw in a postcard.

"Beautiful!” I say amazed as I look at it, focusing especially on the dome, which is really impressive.

I wait, I turn and look around; with me also turns the suitcase that, now, I hold tightly with my left hand.

I am left handed and I like to be, but I also use my right hand very well. Very close, two nuns pass; I look at them: they wear the same monastic habit as the nuns of the Capuchin convent of Corato, where I go to school.

They both look at me, one smiles at me while the other, older, no. Instinctively I look down, I pass the suitcase in my right hand and, fearful, under my eyes, I see them pass and go away.

I breathe a sigh of relief but I cannot stop memories, even bad ones, from resurfacing.

************

First days from the beginning of school, first grade: Sister José is standing in front of the blackboard and tells us to write the letter "a", before the alphabet and to fill in an entire page of the notebook.

She had written it on the blackboard; we pupils just had to copy it and, if possible, write it better.

I had come to fill the third line of the page when, suddenly, a slap on the left cheek and then another on the right they hit me violently.

The pencil falls from my hand and goes to the ground: I cry and do not understand; I look up, the nun hits me again shouting: "That's the devil's hand!”.

He hits me again, one, two slaps: I keep crying and I have no other reaction than to cover my face with my arms.

"Write with your right hand!” he repeats several times as he moves away.

I continue to cry as I look around: my companions are speechless and frightened none of them say anything; they are all afraid, but luckily they are all right-handed.

The nun approaches again, takes me by the collar and drags me out of the classroom.

"In punishment!", and again: "In the corridor, behind the Madonna!”

"Stay here and do not move!” he ordered, pulling me; then, he goes back to class, closing the door behind him.

I am left alone, I cry desperately, and I do not understand why you cannot write with your left hand; what the devil has to do with your left hand, I still wonder now.

My mother had never forbidden it to me, yet she was strongly catholic, even if no longer practicing.

***Later, I'll tell you why it wasn't anymore***

Above all, I did not understand the reason for that ferocious punishment, because such it was, against a six-year-old boy, and moreover inflicted by a nun.

**********

Speaking of nuns: at the time: my father had a sister, Maria, a cloistered nun and Mother Abbess in the convent of Sant'Agata dei Goti in the province of Benevento.

Given his strong sense of humor, he liked to define himself, benevolently, as the brother-in-law of Jesus Christ; since the church defines nuns as his wives.

**********

Crying, I look up at the Madonna; I am behind her, I walk around the statue and look her face: I stop to cry.

I make the sign of the cross and say the Hail Mary: my mother had taught me prayer.

My mother: not sister José.

Despite I also attended three years of kindergarten with the nuns; it was my mother taught me prayer and not her, who was one of them.

Now I am calmer, I look around: the corridor is empty I am alone.

I am about to fix the collar of my apron, which has come undone when I hear footsteps approaching down the hall: I quickly go back behind the statue.

Out of the corner of my eye, I see a nun advancing, slowly; she hears my sob.

Looks up and smiles at me: it is Sister Franca.

He caresses me, takes my hands and asks me why I am there in punishment.

Encouraged by her smile and her caresses, still sobbing, I tell her what had happened to me.

While I speak to her, I look at her face: it is full of tenderness, and in this I see the infinite sweetness that her eyes emanate.

I seem to see the Madonna in her: now, feeling an absolute tranquility in me, I speak to her serenely.

She holds my hands in hers and remains, for a moment, thoughtful. When I have finished telling her what happened, she with a last caress on my hair, ruffling it, tells me "Wait I'll be back soon".

Then, as he goes away, I pass in front of the Madonna looking her in the face.

It is certainly a statue, that represents her, but I also notice in her face what struck me in sister Franca, tenderness.

She is back almost immediately, with a chocolate in her hand.

While I discard the chocolate, she caressing me once again and smiling at me, she says to me, "I speak with Sister José" and, without adding anything else, she goes away.

I have never hated the nun of the slaps, I am not capable of hating; since then, and however, I have not written with my left hand anymore, I am right-handed, only with the pen.

End of bad memory.

************

Few cars parked very few in circulations, only a few pedestrians and some on bicycles; the Cathedral square is half-empty: perhaps for the hour.

Some tired old man with a stick between his legs and a flat cap on his head, sitting in front of a bar or a seat of a political party or a union: they are the only people I see nearby.

Meanwhile people arrive at the stop.

Everyone looks at me; other travelers I think and I hold the suitcase tighter.

The bus arrives and I see, behind the windshield, in front of the driver, the destination sign: Candela; it is mine that is what I have to take.

It is smaller than before and is empty; maybe it starts its run from here, I think.

The driver does not have a company uniform but is wearing only coveralls, which he wears unbuttoned, and a flat cap on his head.

Whistling, the driver gets out and opens the door on is right, turns around the vehicle, and greeting the new arrivals, prides himself on being punctual: as always.

Seeing me, he lifts his flat cap and asks me, "Where are you going? Are you traveling alone?”

”Yes” I promptly reply, and he: "And good the boy! Get in", he orders me opening the passenger door.

"I have to pay for the ticket", I tell him as I put my hand in my pocket to get the money.

"Get in and don't worry”, he says to me.

Everyone stopped to hear, no one had gone up yet.

I get on first and sit, once again as before, behind the driver; this bus has only one door for passengers, on the front.

The seats are completely covered in black leather and are already too hot, the bus, perhaps, had been parked somewhere not in the shade.

After me, a dozen women get on: mostly young girls and a few middle age ones who go to sit in the back.

They all have a handkerchief tied around his head, double wool socks and big boots.

Each of them carries with them a large bundle made of a cotton cloth, of various designs and colors whose corners, diagonally knotted together, act as a handle.

They are laborers, daily peasants; each also has a sickle, the type used to harvest the wheat.

Afterwards, three men also go up, all with flat caps; one of them, limping, in his sixties, helps himself with a stick.

This tells me that, due to his infirmity, he would like to sit next to me.

I immediately move the suitcase and put it on my legs.

Lastly, the driver gets on, closes the door, greets everyone, and sits at the guide saying aloud: "Let's go!”.

We cross the city and then the bus takes the provincial road to the left for Candela.

On both sides of the road, olive groves that flow fast, there is no traffic; we only pass a cart pulled by two mules.

I look at the mules and their harnesses: the latter are all finely worked, especially those of the mule attached between the poles.

The old man, by my side, asks me my name and where I am going.

His voice is hoarse and he speaks slowly; he is a suffering person and therefore I limit myself to responding briefly.

He has the stick straight between his legs; one, the right one, completely stretched out, rigid; hands, holds them crossed on the handle.

Perhaps, from rude, I ask him why his right leg is extended, because limps.

“A war wound in the knee: to this stretched leg", pointing the right, "I no longer have the knee", he replies.

"What war", I ask him; "The first, the great world war", he replies, "I was twenty", he continues after a moment.

"Even my maternal grandfather, Antonio, fought in the First World War, he was in the health service, he was one of those soldiers who, with the red cross on his arm, went to battlefields to collect the wounded", I reply.

"My mother told me", I continue.

The old man nods his head and says, "Maybe he helped me too".

"Maybe", I answer and continue: "My grandfather died a few years ago"; he remained thoughtful and has not spoken any more.

Due to the heat and the short trousers, my legs, in contact with the skin of the seats, sweat and therefore I move slightly from time to time, hoping to have more cooler.

The women, behind, speak loudly and sometimes, on some criticism or comic joke, laugh as loud as they can.

I resume looking at the road: now it is straight on the horizon; the olive groves, little by little, give way to wheat fields.

Beautiful wheat fields, blond in June, swaying when lulled by the wind: a show that fascinates me.

The road to Candela is long and deserted.

The women, behind, meanwhile begin to sing: folk songs of the peasant tradition and immediately afterwards the men also sing, including the driver, but not my neighbor.

A man takes out the harmonica and starts playing: he is good, at least I think, and for me, anyway, that sound is pleasant.

Attracted by the sound I turn around and put my knees on the seat, I get up, look and smile.

Cheerful and carefree people and it shows, yet they are farm laborers, people forced and used to hard work and, perhaps, low wages.

They go to work, who knows where to collect the wheat; hard work, to do under the scorching sun, yet they sing.

Males and females, at least on this bus, are happy.

It seems, especially women, that they have no thoughts or worries.

Surely, I see, they are happy to go and earn even if with hard work, however a job, like that of the reaper.

Now I thought that even the carpenters under my house, while they work with the planer, often sing.

Songs invented at moment by paraphrasing old famous melodies, even from the fascist era, that my father sings often and with pleasure.

I continue to admire the fields while the horizon no longer appears flat.

High hills begin to emerge where, due to the greater force of the wind; the wheat sways more, like a stormy sea.

Borgo Libertà-Torre-Alemanna stops: a small village inhabited by peasants and small landowners where there is a bar, an elementary school, a grocery store, a church and an ancient square tower.

Here my neighbor comes down; instinctively I move to the side to make room for him and he, not without difficulty, gets up and holds out his hand to me, squeezing it tightly.

He greets me with a smile: "Goodbye", he says; "Goodbye", I reply. Slowly, helped by the driver, the old man gets out and goes away.

I never met that man again, however, every time I pass by there, even on the highway, I remember him.

The bus leaves and the women start chatting again.

Two of them, young people, I see that they look at me and after having exchanged a few words they motion me to come closer to them.

One of these calls me by name: "Franco!”

I get up, wondering how she gets to known my name.

"Yes!” she says: "you are Franco the grandson of the mistress Filomena!”

I nod and almost immediately recognizing her voice, I shout her name: "Rosetta! You are Rosetta!"; "Yes, it is me!” she replies.

She gets up and I run to meet her; he hugs me and gives me a kiss on the forehead and one on the cheek, holding me closer.

"You have grown up, you are a young man now; do you remember me?”

“Last year at the farm in Valle Traversa, in Ascoli Satriano, I was also there for the wheat harvest!”

She says looking at her companions who, too, they seem surprised.

"I go back there again, with my companions, tomorrow we begin harvest the oats", he continues, kissing me on the cheek again.

"I'm going to Rocchetta to stay all summer with my grandmother”.

“It may be that we too will come to the farm later on", I conclude.

Therefore, she started, making me sit on her thighs, to tell her friends, the new ones, about the past season.

He tells how in the evening, after work, we had lunch and danced to the sound of an mouth accordion; there was a boy, and also this time too, she says sure, who can play it very well.

Clutching me to her, I feel her breasts press against me.

Rosetta continues her stories, looking for confirmation from me every now and then.

I, with my eyes turned to her companions nod.

Rosetta is a pretty girl: dark brown hair, big bright eyes, dark pupils, full lips not very big, small and pretty nose, upturned.

He is twenty-five, a sincere face, not tall but graceful; he will continue to be a farmhand if he does not find, eventually, a good husband.

I like the position that I am in; unfortunately, however, it does not last long: the bus at a certain point began to slow down and stop.

It stops at the crossroads with a country road, which on the right, going up the hills, leads to the territory of Ascoli Satriano.

Before going down, Rosetta gives me one last kiss: "See you then, bye!"

A farm wagon is waiting for them: there are two mules attached and a man, the carter, who whips in his hand, holds them.

Everyone, except me, gets off the bus.

The farm wagon is a large wagon, of those used for transporting of bundles of harvested wheat from the field to the barnyard where, once great sheaves are ready, the thresher will arrive and be positioned.

During threshing, these same farm wagons are used to transport the straw.

Standing on the bus, I saw the group get into the cart; the women behind, sitting on the platform, and the men leaning on the sides of the cart.

The driver exchanges a few words with the carter, greets everyone and goes up again, off we go.

I see Rosetta, which, with the hand, waving goodbye to me one last time and me respond in the same way as the bus quickly moves away and the chariot is getting smaller and farther away; after a curve, it has disappeared.

Rosetta: I have never seen her again.

************

It is strange but, even now, the people I remember most willingly, and with pleasure, even if with a hint of nostalgia for the past time, are the ones I never met again.

************

Shortly after, we arrive at Candela station: it is on the railway line Foggia-Potenza-Avellino.

I go down and sit on the sidewalk opposite, and I look at it.

It is a country station, far from the village, further downstream and isolated: nothing around, only wheat fields, there is nobody.

The bus is stopped with the engine off and the driver, sitting on the running board, smokes.

I, sitting on the hot sidewalk and with the suitcase between my legs, wait.

Shortly after, while the driver continues to smoke, I stand up, look around and, high up on the hill, I see the village.

A beautiful panorama: a common feature, moreover, to all the villages perched on the hills of the Italian Apennines.

I imagine, beyond, Rocchetta and grandmother's house and the "Foxes Hill" vineyard and the Valle Traversa farm.

On the opposite side, on top of a hill, I see a farm; busies men and women in the yard; below it, further down the valley, grazing animals.

Around always and only fields of wheat, blond with black ears, that here too it sways caressed by the wind.

The air is still warm: I take two steps, back and forth, without leaving the bus and always keeping an eye on the suitcase.

A lizard emerges through the now dry grass and, as a lightning flash, catches an insect, which it immediately devours.

I stay still to look at her: I stare at her, she too is still and turns her gaze in my direction; every now and then, she tilt her head from side to side and, suspended on her paws, breathes quickly.

It does not have a tail: maybe dropped, to escape and not to be, in turn, a victim of some predator.

The Lapalorcia company bus arrives trumpeting, and will finally take me to Rocchetta.

He stops: even now, the driver gets off whistling and greets warmly with each other.

The bus is empty, no passengers.

The two chat for a long time with broad explanatory gestures, alternately moving arms, hands and head cap included.

Sometimes they speak softly, others aloud, and in any case, always in dialect; a laugh, every now and then, revives the conversation between the two.

Then the latter beckons me to go up; I, first, ask to pay the ticket.

In unison, and in a loud voice, they order me to leave it alone; they give me a gift, they say.

There are no controllers on these lines, and this is their gift for a brave child who travels alone.

Therefore, I get on, while they exchange the usual greetings, with respects to their respective wives, after which each takes the lead of their respective bus.

No passengers on the one returning to Cerignola, while it is just me on the one for Rocchetta.

As usual, I sat in front: so, as I said, I can better see the road and the panorama that here becomes more interesting.

The bus is now even smaller and slower; he climbs up the uphill road with considerable effort.

Here the curves are elbow, they are hairpin bends, and each time the driver accelerates to the maximum and sounds the horn for a long time, because there is often no quite visual: you do not see who is coming in the opposite direction.

The sound is typical and distinctive of buses: I like to hear it, to me, it brings joy.

Always uphill, we cross the village; I see donkeys loaded with their saddlebags with men or women in the saddle.

Everyone walks slowly, calm in his or her movements.

In this era, there is no rush: everything takes place naturally and, with the right timing.

I also see women, on foot, walking with a barrel for water on their heads, protected by a rolled cloth, and others with a large basket full of who knows what.

“How they keep them in perfect balance?” I ask myself, and I ask the driver the question.

“It is a question of practicing all the weight on the neck, it is he who bears it, and it must be strong and firm".

To confirm, in fact, I saw one turn around and, to do so, she turned her whole body.

At the exit of the village, on the right, there is a votive shrine with five crosses; the one in the center is larger while those on the smaller sides, to scalar.

Next to, it is the road, which, with a slight curve to the right, immediately starts downhill.

Curves and counter curves, also cranked, follow one after the other.

This time in addition to the horn, the brakes work instead of the accelerator.

Fantastic panorama: with a very wide view, now that we are already at a certain altitude.

A sea of wheat surrounds us and in the distance, I can already see Mount Calvario: a high hill which, seen from here, completely hides Rocchetta and which at the top has a large iron cross.

Downstream, at the end of the descent, there is the San Gennaro farm, a name that is not new to me, and the stream of the same name that runs alongside it.

This farm is not far from the road and, therefore, the people in the yard are now very visible; with them children playing while running, chased by a dog.

We cross the bridge over the stream and the road starts to rise again.

Just before the bridge there is, on the left, and along the road, a huge white rock called in the local dialect: Preta Longa (Long stone), a name of Spanish origin.

Shortly after, on the right, a small path leads, crossing the stream, to the farm.

The bus resumes trudging; at every corner, a horn sound and a gear change, with a double clutch stroke, and the engine roaring again.

The road goes up again: part of the landscape, which I saw from below, I begin now, to see it from above and, gradually, it is becoming more, interesting, and more beautiful.

The sun begins to set: in the middle of a curve, on the right, there is a pumping station of the Apulian Aqueduct that sends water to an underground cistern on the mountain, from which it then, by fall, enters the water pipe of the village.

The caretaker, who is also responsible for the operation he's still, legs crossed, and resting on the jamb.

I see he is enjoying a good cigar.

The driver rings several times to greet him, and then suddenly decides to stop; the brakes screech, a sharp turn, and the vehicle are stopped in a cloud of dust.

They greet each other with transport, it is clear that they are true friends and, probably, of long standing.

I stay on the bus and watch as they chatter; then, the caretaker approaches and asks me my name, and where I come from.

Surprised, I answer hesitantly and he, in return, asks me, "Does your father happen to be called Antonio?”

"Yes!" I reply, “My mother is from Rocchetta; they met during the war”, I prolong, and he “I know!”

“I know your father, and from Corato I also know a friend of his with whom I worked together, for works, in the main channel of the aqueduct”.

"When you come home, bring greetings from me", he concludes.

Having said that, he squeezes my hand, strong almost shattering it and, with a “Hello” Greets me.

We set off again, the road even more sloping, the engine roars. I am standing anxious to see the village at any moment.

We pass in front of a fountain, in a curve, on the left; there are some women who wash clothes and others and others that fill with water the wooden casks tied to the saddle of a donkey.

Behind, the steepest side of Mount Calvario which rises entirely covered with gorse in bloom.

We continue and, finally, after a small road on the right, and a little further on, on the left, the vineyard of "Scialacca": you can see the first houses.

Another curve to the left, the last one, with a small iron cross on the right, firmly planted in the ground, and I see Rocchetta.

************

My father was right when he told me about his first time in Rocchetta.

He was a sergeant and drove a military truck; failing for long time, after Candela, to see him: he wondered where this blessed village was.

He did not even remotely imagine that that village would remain forever in his life.

There he would meet the woman of his heart, the companion of his life: my mother.

************

I am happy, I jump and my heart fills with joy: I will see my grandmother, my uncles, and my cousins.

I imagine when, once there, I will go to the countryside, I will live in the open air, I will play with the dog, I will chase the chickens, and I will go on donkey: wonderful.

I ask the driver to stop in front of grandma's house, which is where I would like to get off, not at the stop down in the square.

He, with a nod of the head, agrees and, without having told him where, stops the vehicle in the right place; thanking him, I greet him and go down.

The bus has gone, I look at the house, the big door is closed, and grandmother is not there.

A little girl passes by and greets me: "Hi Franco!", "Hi Carmela!” I reply.

She smiles at me, and runs away.

The barber opposite, Master Paolo, stops playing the accordion and tells me, “Grandma has gone to the vineyard; she told me that, if you want, you can join her there”.

"La vigna", the vineyard: it is a grandmother's property, in the Foxes Hill district; it is an extensive land, with a small part consisting of vineyards, a rural house on two levels with a grove of elms next to it; he inherited it from his father.

Strange, I wonder: I did not show up and he knows who I am.

I am perplexed, I do not know what to do, and the suitcase is now a problem.

"Leave her here", he says to me, but I do not answer.

I am undecided, and standing at the door.

While I think what to do, I hear the speeches he makes with his clients: they speak of politics, of land to the peasants, of the Communist Party and of the Christian Democrats, and of famous political figures: Nenni, Fanfani, Moro and Andreotti, who for and who against.

Someone speaks of the Americans and says, "Without them, in Italy, and with the war lost, today we would be in shit and, perhaps, we would still be fascists!"

Someone else, however, says that, “The Soviet Union is the workers' paradise; there it is really good, the job is guaranteed and there is no need to emigrate!”

The tones of the discussion are high and, on certain topics, those who think are right raise their voice.

************

This is a characteristic of southern Italy; to talk aloud: always.

Try, today, to sit at a table in a bar, perhaps in the presence of three or four people and you will hear, especially mothers accompanied by children, their screams.

You hear about everything: from what they will prepare for lunch to the defects or merits of their husbands, boyfriends or wives, from the dress that bought that one, to the shoes of that other.

Hearing and witnessing all of this is sometimes nice, sometimes annoying but it is so.

************

Okay, I have decided, I will leave my suitcase at the entrance: I will go.

I start running towards the vineyard, the road is now downhill; I am leaving the village when, from the very last house, on the left, a man is coming out: tall and with a big mustache.

He wears black boots and wears a gray-green uniform, which gives him, it seems to me, the military aspect of an Italian Alpine; the hat in fact, even without the feather, has the same shape.

Seeing me running, he stops to look at me, and in dialect, he calls out to me: “Ne lu npot r zà F-lumena: lu bares, lu mangia carn r ciucc! Andò vaj, accussì r pressa, andò curr?” (Oh, Aunt Filomena's nephew: the Bari, the eats donkey meat, where are you going so in a hurry? Where are you running?).

I, who understand the Rocchetta dialect very well: “To the vineyard, from grandmother”, I answer in perfect Italian, continuing to run.

Immediately afterwards I take the small road on the left, which leads to the vineyard: it is downhill and dirt road.

I run, happy and light, my shirt swells in the wind, I like it and I run faster; I undo another button on the chest, so, the shirt is even more swollen.

I am careful not to stumble: there is a rather deep furrow, dug by the rains, in the middle of the road; while I run, at the same time, I also enjoy jumping on one side and the other.

I take a shortcut, a sort of steeply descending mule track and go down. Halfway up the hill exactly where, during the Second World War, an American plane had crashed, I see the rural house and grandmother's donkey Cerasella tied to an elm.

I finally arrived: now, however, I am out of breath.

The winegrower is sitting on the stone seat next to the door, and very calmly, I see, is filling his pipe with tobacco, which he has taken from his waistcoat; he looks at me and, surprised by my arrival, does not recognize me.

I do not see grandmother, before looking for her I stop and try to catch my breath.

The man, old, certainly over eighty, with a big white mustache, is dressed in a gold-colored corduroy suit, a white shirt, waistcoat and handkerchief tied around his neck, both black.

As soon as he has lit his pipe, taking the first puff, he beckons with his hand, indicating where Grandma is: down, to the hens.

Before moving to meet her, I keep looking at him: his shoes are high, massive and spiked, for the countryside, on the head a sort of panama-type straw.

The pipe has a clay cooker and depicts the head of an owl, the barrel of the mouthpiece, curved and rather long, in bamboo.

The man, smoke and wait; beside him he has a stick and a bundle in which, I think, there are his clothes to wash.

Down in the stable, I hear grandmother shouting: a hen, left outside, does not want to enter; I quickly, following her and pushing her with open arms, I force her, to enter in the chicken coop.

Grandmother saw me: not a word, she is angry; stopped, knots the handkerchief on her head then closes the door.

I helped her to put against each side of the door what remains of two machine guns: body and barrel, in one piece and very heavy.

These had been two of the machine guns of that American plane, loaded with soldiers and auxiliaries, which had fallen, touching the house, one evening in October, exactly on the 14th, in 1944.

************

My mother had already told me about that tragic event.

She was the first to feel from the village: first the roar of the engines, which grew louder, and then the impact.

From the balcony, addressed by the strong glow that pierced the darkness, she understood: the plane had fallen right next to, if not even on the house.

There was in the countryside that evening, in the company of the winegrower, her younger brother and her, older sister, fearing the worst and winning the resistances of grandmother, she had rushed there at breakneck speed.

She was one of the first, with her heart in her throat, to run. Fortunately, the little brother and the winegrower were safe.

The house had been barely touched, as the plane had struck a hundred meters ahead, halfway up the hill.

The aircraft, or rather what remained of it, was destroyed; several bodies of men and a woman in uniform scattered all around.

Among the many corpses there was someone who was gasping; a girl with a split skull and open eyes, my mother said, seemed to be still alive, but she was dead.

He never told me other details of the tragedy, not even as an adult. I always understood that for her, a 24-year-old girl at the time that had been a very sad experience and, the scene, a gruesome sight.

A tragedy, one among many of that period, he always told me.

************

After having closed the door well, in the semi-darkness, we went upstairs: there is a wooden staircase to go up; once outside I see the winegrower, quiet and still sitting, continuing to smoke.

I was very impressed by his attitude, calm and patient, in waiting for us; he has to go home, but he seems to be in no hurry and in fact, as I have seen, it has none.

************

Nobody was in a hurry at the time; today everyone runs, except for some elderly people: included me.

************

The truth is that he cannot leave without first saying goodbye and took leave of grandmother.

Therefore, after quitting smoking, turning to grandmother he says, "So, mistress Filomena, I'm going away, see you tomorrow".

Without waiting for the answer, he emptied his pipe, tapping it lightly on the seat, gets up and put it in his pocket.

Takes the bundle and, aided by the long shepherd's stick, set out on foot.

I thought the climb to the village will be tough for him, but that does not seem to bother him.

Grandmother still has something to do and I take the opportunity to play: I tickle the mustache of the donkey, who sneezes as a reaction, I let the dog chase me several times, also trying to hide, in vain, among the elms.

The dog, which I already saw and caressed last year, immediately recognized me, coming towards me wagging its tail and without barking.

Immersed and almost hidden the trees there is a wooden shack, painted gray, on iron wheels: there, I play hide and seek with the dog.

This has no difficulty in finding me, although I remain in absolute silence.

************

My grandfather had planted that thick grove years ago; he had been far-sighted, since in the whole area there were not, and they are not there yet, other shade trees.

************

There are huge clouds in the sky now: cirrus, I think they are called; I lie down on the grass and fantastic in imagining the outline of some of these clouds.

In one of them, I see the profile of a lion's head, in the other that of a dog, I put my hands in front of my eyes, mimicking binoculars, so as to eliminate the remaining part of each cloud.

Suddenly a pair of hawks, buzzards I think, grabs my attention.

I remain as if enchanted to admire them, how mighty they are and elegant, fly high in the sky.

They are huge and sometimes-fly low with their wings spread out and motionless; they fly in circles and make wide turns, emitting frequent calls.

Then, still taking advantage of what remains of the updraft, after a while, they climb higher and move away to the west.

The sun is low now, sunset is near, and we must hurry: grandmother has finished her chores and calls me.

I help her harness the donkey, putting her saddle and then her saddlebag on her, filled one bag with fresh chickpeas and the other with a small basket of sour cherries.

Grandmother, meanwhile, closes the door hiding the key in a secret place and, smiling at me, said to me: "Let's go"; the only word turned to me up to that moment.

Approached the donkey to an embankment grandmother rides.

With an "Iah!" and a blow of the bridle on the big ears, the donkey, shaking her big head, she moved, walking, I, behind, I follow on foot.

The road, first in a false plane, after a curve to the left, begins to climb with a steep slope; now I see Rocchetta.

From this point, the panoramic view is that of a small village that surrounds and climbs up a steep hill, like a pyramid, with the historic center and the ancient area at the top, which was hit by the earthquake of the 1930, surmounted, in turn, from an ancient castle.

************

I am always ecstatic, every time I happen to see the country from that angle even if, today, it is no longer the fascinating one of the time I am talking about.

************

There is silence around us; only the slight noise of the shod clogs of Cerasella walking slowly in the pass.

I look at the village: now some lights in the houses it turns on and the road, meanwhile, becomes increasingly steep and tiring.

I begin to breathe faster.

Therefore, I take the tail and attach myself, wrapping the tip around my hand I let myself be pulled.

The sun, meanwhile, has set behind a hill; there is still enough light: we are not quite at dusk.

In the distance, the sound of a bell is heard: the hour of Vespers.

The grandmother, from a pocket of her long skirt, takes the chaplet and begins to recite the Holy Rosary.

I, still attached to the tail, continue to look at the village; many other lights have come on: from a distance, it now looks like a nativity scene.

We are about to leave the dirt road when, all of a sudden, I feel that the donkey pulls up its tail with force.

I turn around and see that this is defecating.

I move quickly to the side so as not to be hit by his excrement: a stench hits me, instinctively, I turn my head and, with the other hand, I squeeze my nose.

Cerasella continues to walk, phlegmatic and constant, with her step; we are now on the provincial road: it is recently paved, beautiful, wide and almost flat.

Shortly before, my grandmother made me climb onto the withers in front of her.

I am higher now; I have never been on horseback, not even on a donkey: the bare legs due to the short shorts, in direct contact with the animal's body, allow me to feel the movements of its muscles.

I do not know why but at a certain point, and catches me off guard; the donkey quickly lowers her neck until her nose almost touches the asphalt.

He sneezes hard, his body vibrates all over and I am slipping on his head; the grandmother quickly holds me back, wrapping my waist.

I got scared; suddenly in front of me I saw the void.

We enter the village and, from the first houses, I see people sitting at the door: grandmother greets everyone, and everyone responds to the greeting, while some follow up with their comment, addressed to me, seeing me in that rather precarious position.

To these, grandmother makes follow, diplomatically, dry reproaches and a different greeting.

************

To Grandma, you cannot make jokes and comments that she does not like to her, she never accepted them; it sends you to the devil without thinking twice, and it was valid for everyone.

Obviously, only in a strict dialect: its language.

The beauty of a small town, among other things, is precisely this: everyone knows each other and everyone says goodbye because, often, they are also distant relatives.

Here the cousins of the fourth or fifth degree of kinship still consider themselves relatives; in fact, I noticed that, especially men, greet each other, addressing each other confidentially with, "Uè parè!" (Oh Relative!).

The young women, among themselves, call each other by name; when on the other hand, they are addressed to elderly women and among older women, and they always use, confidentially, the noun "zà" (aunt).

In Corato, instead, among men, the noun “cumpà” (godfather) as mentioned before, among women, the noun “cummà” (godmother).

All that has been said, I consider it a living more on a human scale and that is why, especially today, I am convinced that these small villages, scattered throughout the Italian Apennines, should be visited and valued.

Here, despite everything, yes it still lives as it once was on a human scale.

They are ancient villages full of history, art and monuments from all eras.

Their churches, and their small baronial castles, are real jewels architectural.

In the beautiful seasons, their historic centers are filled with flowered balconies, and those narrow streets paved with cobblestones or huge and heavy paving stones, often in lava stone, have a magical power: to relax your body and calm your mind; not to mention the genuine food, and the pure air you breathe there.

Today we would have a lot to learn to live better, let us get to know them.

************

We arrive at the house when it is almost dark; Cerasella has stopped right in front of the staircase.

I thus observe once again how animals, all of them, know how to get used as usual, both towards man and towards things.

Without grandmother helping me, to dismount, I lift my right leg and step over the animal's neck; I slightly twist my torso and, holding my right hand to the saddle, I let myself slide and, slowly, touch the ground.

Grandma is also dismounted and runs to open the stable while I move the donkey to tie it to the iron ring, placed on purpose, there near the stable door.

The donkey does not move, it knows, it has to wait to be unloaded from its load.

While waiting, while I am scratching his forehead, she suddenly, taking me by surprise, rubs her nose against my chest; she wants to scratch herself, for the itch caused by the harness and so has soiled my clean shirt.

Having removed the saddle I put the big head on him, let him in and tie him to the manger; grandmother brings him a bucket full of water and she quenches his thirst, drinking most of it.

We govern it by putting hay in a corner on the ground and oats mixed with straw in the manger; the donkey eats greedily, plunging its snout into the straw.

While she eats, I stay to watch her; the oats mixes with the straw, and the mouth fills up more and more: he chews hard and looks at me, slightly lowering his big ears.

We take our things, turn off the light and close the barn: the day is over for Cerasella.

We go down to the house from the back, once on the floor below the grandmother opens the large door from the inside that overlooks the main street of the village, Corso Umberto, and closes the window.

In the meantime, I reopen and look out the door, the barber is still open; does not make beards or cut the hair, and instead he has the accordion resting on his legs and, every now and then, he plays: his clients, it seems to me, they talk again about politics

I go out, through the course, and I approach: I have to take my suitcase.

The barbershop is illuminated by two light bulbs, one in the center of the ceiling and the other on the mirror; on the right, aligned, the chairs for waiting customers and on the left, the typical barber's chair, in front of the sink and the mirror attached to the wall above.

Topic on which, this time, I hear them discuss is the municipal administration.

The mayor is the main subject but there is no lack of criticism or appreciation towards of some area deputy and the councilors of the village hall.

A look of understanding with the barber and, from where I he left it, I take the suitcase; I thank Master Paolo and as I leave, I greet everyone: they all answer in unison.

At my "good evening", everyone follows, in their dialect: "Buona sér lu bàres!" (Good evening, Bari).

I come home while grandmother is busy making dinner.

He is melting the pork lard for the sauce in a pan; grandma uses it instead of olive oil.

The pasta is already in the pot, on the fire, I set the table.

Following his instructions, I spread out the tablecloth and put on it cutlery, glasses, water, wine and a magnificent loaf of bread taken from inside the "matrella" (sideboard), together with a very fragrant "caciocavallo" (aged cheese), already cut, and to an inviting plate full of raw ham cut by hand in thick irregular slices.

While waiting for it to be ready on the table, I walk around the house in search of the memories of the previous summer.

I look out from behind the window, and push aside the white silk curtains made from one of the parachutes of the fallen American plane.

I look at the road: the stroll or the "Struscio" as they say here begins; middle-aged men and women are walking around, mainly teachers and public employees.

Even the only police officer of the village walks.

Few young males, mostly university students, some of whom are notoriously out of course, even fewer girls.

Grandmother calls me: “dinner is ready, come and sit down!” it is the second time that, today, she speaks to me; as I sit down she puts in front of me a nice plate of pasta, drawn in the shape of a snail, with tomato and basil sauce and a lot of "Pecorino" cheese (made with sheep's milk) on top.

The dish smokes, I smell and eat greedily: what a perfume and what a taste that pecorino cheese.

The cat, certainly attracted by that delicious scent, begins to meow rubbing against my legs, not against those of my grandmother.

She, while eating, with the other hand she takes the broom, which she had previously placed at his side, to drive him away.

The animal evidently, already knows the grandmother's intentions and fled anticipating it; perhaps to move us, he keeps meowing.

I ask, "Is it because it is hungry that the cat meows?” without looking at me grandmother answers me only saying that, "He must eat the mice and, in any case, he must always eat after us!".

I ask, "Grandmother, where are the uncles?"

The uncles: Paola, elementary teacher, Ferdinando university student of the veterinary faculty in Naples, Lina (diminutive of Angela) homemaker and Armando, the youngest, farmer and tractor driver.

All four unmarried, they live in the house with her and, especially the two females, subject to her strict rules.

He drinks some wine, passes the napkin over his mouth, and replies: "Ferdinando is in Naples, Armando has started working with the thresher, Paola and Lina are with relatives".

"Those two should be home by now!" she continues nervous making himself tremble his chair, which is also sturdy.

Sign of a growing nervousness, due to the delay of the daughters, grandmother unties and knots several times, not before having fixed her hair and in particular, that rebellious tuft that always falls on her right eye, her kerchief headdress.

The two of us have finished dinner and Grandma seems to have calmed down; he gets up removing only the dirty dishes and leaving the table set again.

Out of the corner of his eye, it seems to me, he sees the cat crouched on a chair; she quickly takes the broom to hit him, but he is faster than she is, and with a leap, runs away.

"Smiling at me, he says, “this time he it was faster", I smile too glad I earned a smile.

Still sitting at the table I watch her go about her chores: she is small, petite and full of energy, she is about sixty years old, with a firm and authoritarian character.

Woe to contradict him, but overall fundamentally good even if scarcely affective.

I have always believed she missed her husband a lot: my grandfather, who died of bladder cancer at the age of seventy, in 1950.

************

I do not know much about him except what my parents had told me over time.

My mother, very close to him, said: "Grandfather was sixteen years older than grandmother and, among the guests at her baptismal party, she then expressed her convinced decision with the exact words:" I will wait and, I will marry her".

So it was.

What may have struck grandfather's sensitivity at that juncture, what he could have thought, and what clicked in his mind, is difficult if not impossible to define.

As I have already said, he had been a conscript, in the military health service, long before the great world war and, then, in this, he had participated as a recalled.

He was a landowner, rancher and with several agricultural properties scattered throughout the territory.

The San Gennaro farm in the territory of Rocchetta in front of "Preta Longa": remember?

A large plot of land in that of Candela, near where today there is the motorway exit, then the farm Valle Traversa in the countryside of Ascoli Satriano.

In addition to the normal production of cereals, grandfather also raised mainly cattle and saddle horses.

The latter were also requested by the then Royal Italian Army, after a selection visit by a military veterinary commission: there was still cavalry at the time.

Mother still said that when and if it happened that a horse was gored, since they grazed in the wild together with the cows, and for this he died, grandfather made him bury.

In Rocchetta, even today, horsemeat is not consumed.

Another fact she told me, because she lived it in the first person, is when, on a heavily rainy day, she, still a teenager, on the in a gig guided by their grandfather, they crossed the San Gennaro creek swollen by water.

The strong current and the great mass of water were about to carry them away, with all the gig and the mare if, the latter incited to advance, with an enormous effort and a great momentum, had not managed to ford the stream and put them in safety, even if completely wet.

************

In November 2017, I got to see, on Face book, some photos of the torrent in flood, and in the same spot.

The mass of water that can be seen rapidly descending from the hill is truly impressive.

Mom said that grandfather would never have dared to cross that torrent, so impetuous at that moment, if he had not known the potential of that mare he was very fond of.

Mom also emphatically said that when the grandfather came home to the gig, it was the mare that knocked on the door with her hoof.

After 8 September 1943, with the retreat of the Germans, and the arrival of the allies in the area, the grandfather had begun to have problems, like all the owners and employers of the time, with the workers.

He had eight permanent employees plus a dozen a day; these, also due to the stupid ideologies of the time, began to resort more and more often to the unions, abandoning their jobs and leaving animals and household items unattended.

To increase her resentment, mom said that this was, above all, the area of the famous trade unionist Di Vittorio.

Then he continues that, with the fall of Fascism, people started talking about land again to the peasants; the communists, who had previously become fascists, are back to being communists again and this, in the long run, and scared the grandfather.

They frightened him, and even threatened him, he said, to the point of to push him, for fear of losing them, to sell several properties, the proceeds of which in money, a considerable sum for those times, grandfather has deposited at the post office.

Being forced into this, he said, must have been, I can testify that my mother was strongly convinced of it, the trigger of the disease that would lead her father, in a short time, to death.

The money then, with the subsequent devaluation of the Lira, was barely enough for the necessary care until death; as a consequence of this, for the family, a short period began, clouded by some misunderstanding.

Regarding the retreat of the Germans, this fact concerns grandmother, mother told me that, while they crossed the village in columns on both sides of the course, grandmother had bolted the door and, taking up her rifle, sat inside ready to fire and sacrifice to protect the four daughters.

My father, on the other hand, said that, once he met and attracted by that girl his neighbor, he immediately tried to establish an excellent relationship with his grandfather, and he succeeded, on the contrary of with grandmother.

The common knowledge to both of them of personalities of the time, such as large merchants and grain brokers, also from Corato, had facilitated my father's relationship with his grandfather who, in a short time, had transformed into a deep and mutual respect.

The friendship, also born by virtue of his military status of sergeant, with the Marshal of the Carabinieri (Military Police) of Rocchetta had helped to dissolve any reservations of his grandfather towards him.

However, my mother continued on this subject, said grandfather, before granting consent, to his engagement with she had made ask, through the archpriest, information about him from a priest in Corato.

In addition to having seen him in some rare photographs, I, of my grandfather, have only one memory of him, direct, true and indelible in my mind: a two-year-old child, in the arms of an aunt (Lina), I think, dressed in black.

This, moving my outstretched hand, invites me to greet my grandfather with a kiss: a man with a big mustache, who is, I see, stretched out and motionless, in a black suit, on a large bed and with so many people around.

|

|

Biblioteca

|

Acquista

|

Preferenze

|

Contatto

|

|

|

|